More than 60 million American women have heart disease. "The statistics haven't improved enough," a women's heart doctor told us.

“Here’s How I Knew I Had a Heart Blockage”: A Patient Story of a Good Catch Without Symptoms

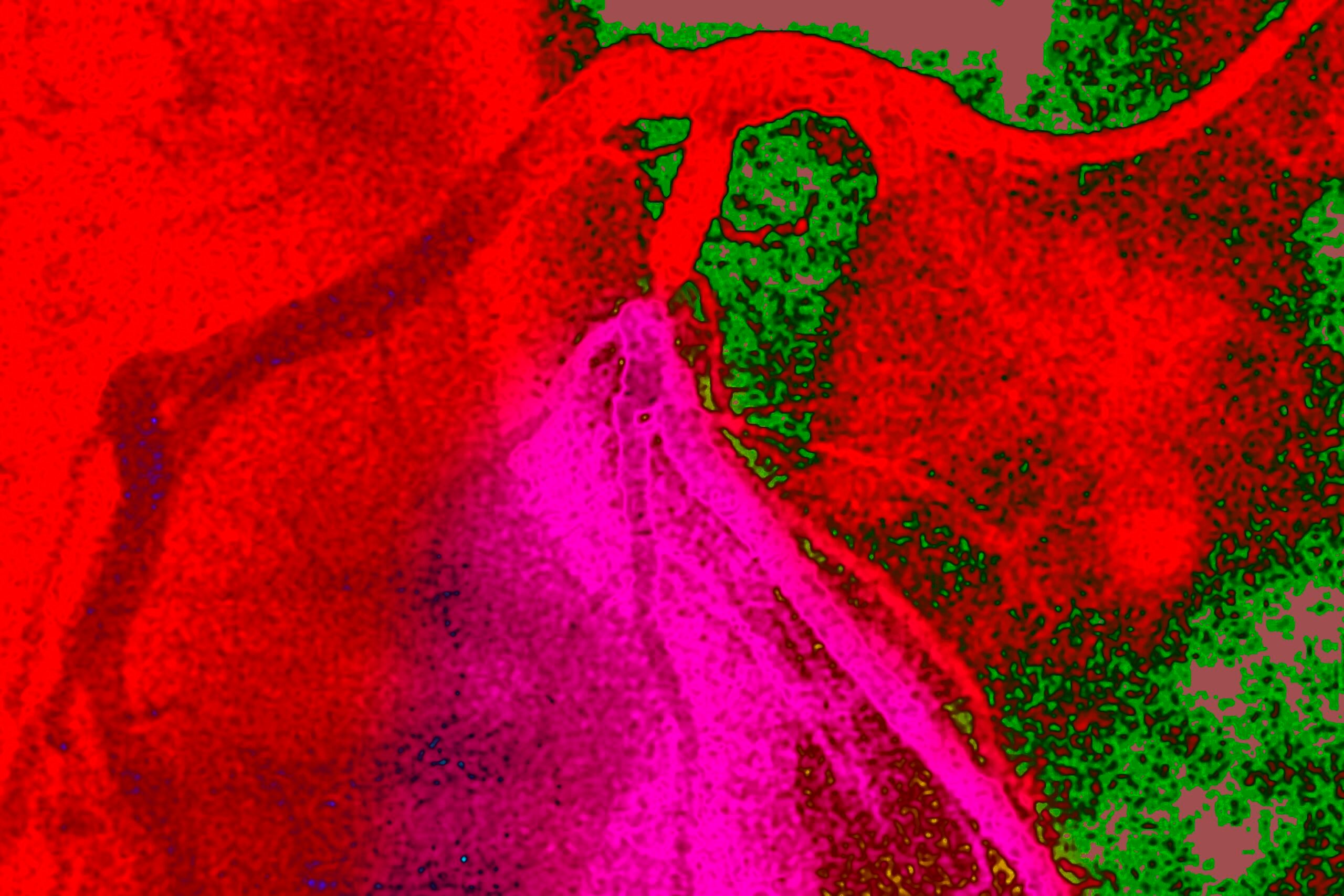

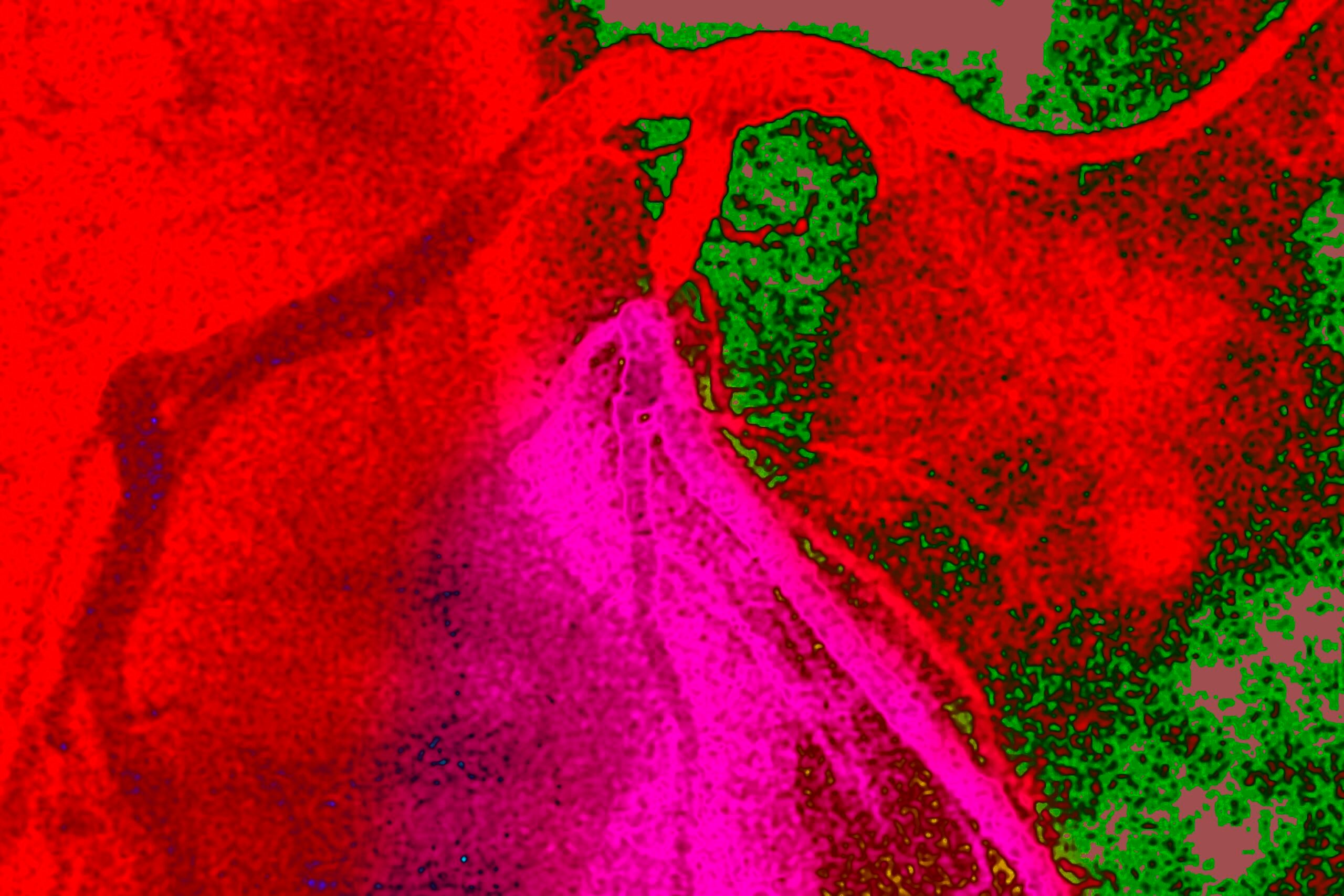

A heart blockage occurs when the coronary arteries, which are vessels that supply oxygen-rich blood to the heart muscle, become narrowed or completely blocked by a buildup of plaque. This plaque is made up of cholesterol, fat, calcium, and other substances found in the blood. Over time, this buildup, known as atherosclerosis, can quietly progress, sometimes without any noticeable symptoms, until it results in something life-threatening, like a heart attack.

Jane Lombard, MD, a board-certified cardiologist and medical director of the Women’s Heart Center at El Camino Health, explains that atherosclerosis isn’t one-size-fits-all. “People can have it and live for many, many years—even decades—without any intervention and have a very productive life,” she says. “But in some, the plaque ruptures, and that causes a heart attack.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), about 805,000 Americans have a heart attack each year. Risk factors include high cholesterol, smoking, high blood pressure, diabetes, a sedentary lifestyle, and, in particular, a family history of early heart disease—specifically, a male family member who had a heart attack in his fifties or a female member in her sixties.

Women’s heart blockage symptoms are often missed

One of the most dangerous aspects of heart disease? The heart blockage symptoms can be subtle, especially in women. While many people associate heart problems with crushing chest pain, women are more likely to experience subtler signs like shortness of breath, unusual fatigue, indigestion, jaw or neck discomfort, or nausea.

“I’ve had women come in with what they thought was terrible heartburn, and it turned out to be a heart attack,” Dr. Lombard says. “A lot of women never think they could be having a cardiac issue. It doesn’t even cross their minds.”

This misconception is part of a much larger awareness gap. Many women believe their greatest health risk is breast cancer, but that’s not the case. “Survivors of breast cancer are now more likely to die from heart disease than their cancer,” Dr. Lombard explains.

The Red Dress Campaign, launched nearly 25 years ago, was created to raise awareness that heart disease is the leading cause of death for women. Yet even now, Dr. Lombard says, “Women are still underdiagnosed and undertreated,” adding: “The statistics haven’t improved enough.”

The link between pregnancy and future heart risk

For women who’ve had children, part of the problem starts during pregnancy. Dr. Lombard emphasizes that complications like preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, and recurrent miscarriages are now recognized as early warning signs of cardiovascular risk later in life. “Pregnancy is the biggest cardiovascular test your body will ever undergo,” she says. Many women are never asked about their pregnancy history when being evaluated for heart disease, despite the clear connection between obstetric complications and future cardiovascular risk.

Another major challenge lies in how women experience the healthcare system. Many don’t feel heard. A recent El Camino Health survey found that 59% of women believe a doctor of the same gender better understands their experiences, symptoms, and concerns, compared to just 36% of men. (UCLA research in 2024 found that patients with female doctors also experience better outcomes and longer lifespans, on average.) Unfortunately, this kind of heart care can be hard to find as only 17% of cardiologists in the US are women. El Camino Health’s Women’s Heart Center was created specifically to address the unique symptoms, risk factors, and healthcare needs of women.

Prevention starts early

“Everyone, regardless of risk, should live a heart-healthy lifestyle,” Dr. Lombard says. “That’s easy to say, but hard to do.”

Still, she emphasizes, the earlier you begin a prevention-focused approach, the less atherosclerosis you’ll develop over time. Dr. Lombard recommends that everyone have their blood pressure checked in their twenties, and get a cholesterol screening in their thirties—even earlier if there are risk factors like family history or adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Ahead, we share the story of Ann S., a 53-year-old woman from California who had no outward symptoms of heart disease and discovered she had blockages in her heart that required triple heart bypass surgery. Her story is an important reminder that you don’t have to feel sick to be at serious risk.

How I Knew I Had a Heart Blockage

By Ann S., as told to Dr. Patricia Varacallo, DO

I had a few known risk factors: elevated cholesterol and a family history of heart disease. But I had no heart blockage symptoms—no chest pain, no shortness of breath, not even fatigue—when I found out I had serious blockages in my heart. The news blindsided me. Before I knew it, I was preparing for triple bypass surgery.

A family history of heart disease

My dad had a triple bypass at 47. He wasn’t overweight or visibly unhealthy. He hiked and camped regularly. One day, he started having chest pains and went to get checked out. After a series of tests, doctors discovered significant blockages in his coronary arteries, and he was scheduled for triple bypass surgery.

A triple bypass is a major procedure where surgeons use healthy blood vessels—often from the chest or legs—to create new pathways around three blocked arteries, allowing blood to flow more freely to the heart muscle.

Not long after my dad’s procedure, about a year later, his older brother died suddenly of a heart attack. He was only in his early fifties. That was the extent of our known family history on my father’s side. My mother, on the other hand, lived to a decent age without any heart issues.

Watching my cholesterol numbers

I had kids young and stayed busy raising a large family. During checkups in my twenties and thirties, doctors would do basic blood work, and my cholesterol would come back elevated. I was told that since I was young—and because I was often breastfeeding—my cholesterol levels could be temporarily skewed.

And that’s true, to an extent. Estrogen has a protective effect on the cardiovascular system, and hormonal changes during pregnancy and postpartum can influence lipid levels. But this reassurance meant my lab numbers were always noted and then dismissed—not quite alarming enough to act on.

That changed when I turned 50. With the onset of menopause, my estrogen levels dropped, and I knew that shift increased my cardiovascular risk. Menopause is often a turning point for women’s heart health, since estrogen plays a critical role in maintaining the flexibility of blood vessels and helping regulate cholesterol.

Finding the right cardiologist

I made it a point to find a cardiologist who specializes in women’s heart health. I didn’t want my concerns dismissed just because of my age. After doing some research online, I found Dr. Lombard at the Women’s Heart Center at El Camino Health and booked an appointment.

My initial workup showed what I expected: high cholesterol. She started me on a low-dose statin, and we decided to monitor things slowly. But during a follow-up six months later in October 2024, my husband suggested I ask for a coronary calcium scan. This test uses a CT scan to look for calcified plaque in the coronary arteries. It’s a direct marker of atherosclerosis, and it can reveal cardiovascular risk that routine blood tests don’t always catch.

A shocking test result

When the results came back, my calcium score was over 1,300. That number was so high, I thought it had to be a mistake.

To put that into perspective, according to the Mayo Clinic:

- A score of 0 means no calcified plaque is detected in the heart, indicating a low risk of heart attack in the near future.

- Any score above 0 suggests some degree of plaque is present. The higher the score, the greater the risk.

- A score between 100 and 300 indicates a moderate amount of plaque and a relatively high risk of heart attack or other cardiac events within the next three to five years.

- A score over 300 signals more significant coronary artery disease and a heightened risk of heart attack.

That result launched a cascade of further tests. First came a stress echocardiogram, which combines treadmill exercise with ultrasound imaging of the heart. After exercise, some areas of my heart weren’t contracting as they should—signs of potential ischemia, or reduced blood flow, likely due to narrowed arteries.

Next came the angiogram, which is a procedure where a catheter is inserted through the wrist or groin to inject dye into the coronary arteries while X-rays track blood flow. It confirmed everything: I had several significant blockages. I needed bypass surgery.

Triple bypass surgery and recovery

My triple bypass was scheduled for the third week of January 2025. By then, I’d already paused my usual workouts—strength training and water aerobics—out of caution. Water aerobics, especially, had become less appealing because it was winter and I didn’t want to risk cold exposure while I was dealing with a potential heart issue.

Surgery was intense. I spent six days in the hospital. Waking up in the ICU was especially tough, but I’d done enough research to know that the recovery would be hard. I was as prepared as I could be.

My doctor prescribed a chest binder—an elastic wrap that keeps everything snug around your rib cage. For women, the weight of breast tissue can put added strain on the healing sternum.

I also had to follow “sternal precautions,” which are rules about arm movement to avoid stressing the chest. I wasn’t allowed to push myself out of chairs, lift anything over five pounds, or reach both arms overhead. We bought a recliner so I could rest at night without having to lie flat, which is often uncomfortable post-surgery.

And of course, I still had a household to run. I have school-aged children and a packed family schedule, so before the surgery, I created a detailed list of who needed to be where and when: school drop-offs, dinners, activities. It helped my family—and me—stay grounded during the chaos.

Where I am now

Today, two months after my procedure, I’m still recovering. I get tired more easily than I’d like, and I’m still sore in spots. I take pain meds sparingly now.

I was cleared to drive at the six-week mark, but turning to check my blind spot or reaching for the steering wheel can still be uncomfortable. I let others drive when I can.

There’s a delicate balance in recovery. You’re not supposed to sit around all day, but doing too much can wipe you out. I’ve had days when I felt good and tackled a bunch of household tasks, only to crash in the afternoon. I’m learning to pace myself.

I was on a powerful diuretic for the first month after surgery to prevent fluid retention, which can stress the heart. I’m glad to be off that now because getting up to use the restroom multiple times a night wasn’t fun. I’m still on a beta blocker to help manage blood pressure and ease the heart’s workload, but my doctor hopes to taper that soon.

Most of what I’m on are the same medications I was taking before surgery.

Soon, I’ll be starting cardiac rehabilitation, a medically supervised program designed to help people recover after a heart attack, bypass surgery, or other heart conditions. It typically includes a mix of monitored exercise, nutrition guidance, stress management, and education to help reduce the risk of future cardiac events. I’m hopeful it will help me ease back into daily life and regain my strength.

What I want other women to know

If there’s one thing I’d tell other women, it’s this: Find a doctor who truly listens. One who knows that heart disease in women can look different than it does in men. And if you’re not getting answers, ask around. Nurses often know who the best doctors are. Don’t settle and don’t wait for heart blockage symptoms.

There’s also something I didn’t know until Dr. Lombard told me: Certain pregnancy complications—like preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, or recurrent miscarriages—are now recognized as independent risk factors for cardiovascular disease in women. I’ve had multiple pregnancies, and not once did a doctor connect any of that to my long-term heart health.

The reality is, women are still underdiagnosed and undertreated when it comes to heart disease. That needs to change. And it starts with awareness—knowing your risks, trusting your gut, and advocating for the care you deserve.

What to do if you suspect you have a heart blockage

If you’re experiencing symptoms like chest discomfort, shortness of breath, fatigue with exertion, jaw or neck pain, or persistent indigestion, it’s critical to seek medical attention. Call 911 immediately if your symptoms are severe, sudden, or accompanied by nausea, sweating, or difficulty breathing.

For less urgent concerns, schedule an appointment with your primary care doctor or a cardiologist, who may recommend tests like an EKG or stress test to evaluate your heart health. Early detection can make all the difference.

About the expertJane Lombard, MD, is a board-certified cardiologist and the medical director of the Women’s Heart Center at El Camino Health, where she has been serving patients for over 20 years. A graduate of Stanford University School of Medicine, Dr. Lombard specializes in women’s heart health and preventive cardiology, with a strong emphasis on community outreach and education. In addition to her clinical work, she serves on El Camino Health’s ethics committee and is deeply committed to advancing compassionate, patient-centered care. |

For daily wellness updates, subscribe to The Healthy by Reader’s Digest newsletter and follow The Healthy on Facebook and Instagram. Keep reading: